Unions have been a prominent feature in the American labor market for many decades. Unions are organizations that represent the collective interests of employees in a specific industry or profession. They negotiate with employers to ensure that employees receive fair wages, benefits, and working conditions. One of the key components of union membership is the payment of union dues.

If you’re thinking about joining a union, or if you’re already a member. You may already hear the term “union dues”. But what are union dues, exactly, and why do they matter? In this article, we’ll explore what union dues are, how they’re calculated, and why they’re important for both unions and their members.

Union dues are fees paid by union members to support the activities and goals of their union. These fees can vary depending on the union and the industry, but they generally cover the costs of union administration, collective bargaining, and other union-related activities. Union dues can also fund political campaigns or other advocacy work related to workers’ rights and social justice issues.

The funds collected from union dues at Calexico Unified School District are used to support the union’s various activities, including:

- Negotiating with employers for better wages, benefits, and working conditions

- Representing members in labor disputes or grievances

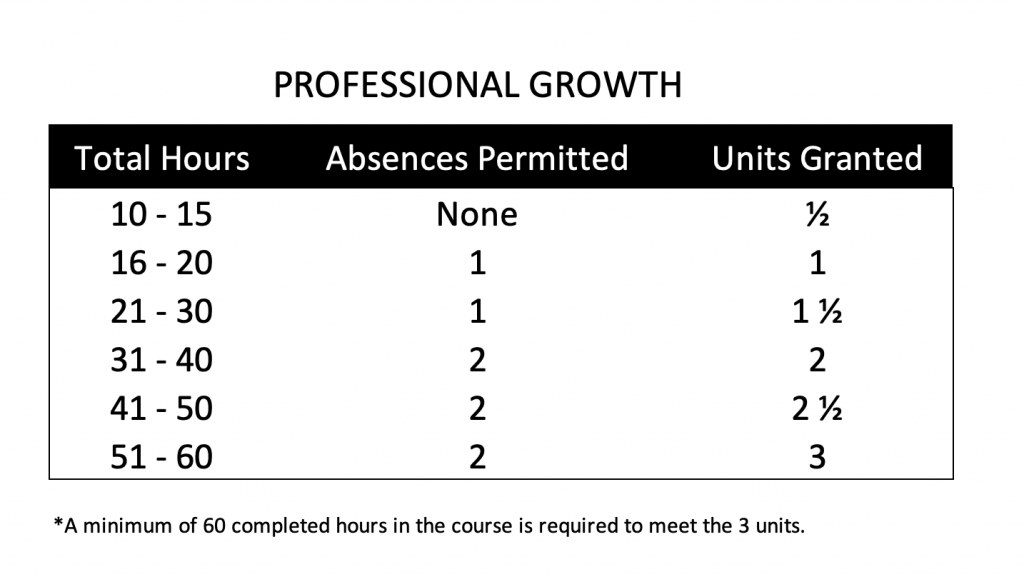

- Providing education and training programs for members

- Advocating for labor-friendly policies at the local, state, and federal levels

How Are Union Dues Calculated?

The way union dues are calculated can vary depending on the union’s rules and bylaws. Some unions charge a flat rate per member, while others calculate dues as a percentage of a member’s wages or salary. In some cases, unions may also charge initiation fees or assessments for special projects or campaigns.

The Importance of Union Dues

Union dues are critical to the continued success of labor unions. Here are some of the reasons why they matter:

1. Funding for Collective Bargaining

One of the most important roles of unions is collective bargaining. This process involves negotiating with employers on behalf of union members to secure better wages, benefits, and working conditions. Union dues provide the funding necessary to support this bargaining process. Without this money, unions would not have the resources needed to effectively negotiate with employers, and the bargaining process would suffer.

2. Protection of Employee Rights

Unions play a vital role in protecting the rights of employees in the workplace. They represent members in grievances and disciplinary proceedings and advocate for fair treatment and due process. Union dues fund the resources necessary to provide these services to members. Without funds, unions would not be able to provide the necessary legal and financial support to their members.

3. Professional Development and Training

Many unions provide education and training programs to their members. These programs help members improve their skills and knowledge in their respective fields, making them more valuable employees. Union dues fund these programs, which can help members advance in their careers and earn higher wages.

4. Political Advocacy

Unions advocate for policies that benefit working people, such as better wages, workplace safety regulations, and healthcare access. Union dues fund the resources necessary to support these advocacy efforts, including lobbying, political campaigning, and grassroots organizing.

The Controversy Surrounding Union Dues

Some people argue that mandatory union dues are unfair because they force workers to support an organization they may not agree with or want to be a part of. These individuals may feel that they should be able to negotiate their own wages and benefits without the involvement of a union.

The right-to-work movement

The right-to-work movement is a political and ideological movement that seeks to limit the power of unions by making it illegal for unions to require workers to pay dues as a condition of employment. Right-to-work laws have been passed in several states in the US, and they are often supported by conservative politicians and business interests.

In 2018, the US Supreme Court ruled in Janus v. AFSCME that mandatory union dues for public sector employees were unconstitutional. This decision has been controversial, with some arguing that it weakens the power of unions and undermines workers’ rights to collective bargaining.

- Critics against the right-to-work movement argue that right-to-work laws weaken union power and benefit corporations by limiting the labor union budget.

- Research at the Economic Policy Institute shows that states with RTW laws see higher employment but lower wages for workers.

- The biggest difference between workers in RTW and non-RTW states is the fact that workers in non-RTW states are more than twice as likely (2.4 times) to be in a union or protected by a union contract.

- Average hourly wages, the primary variable of interest, are 15.8 percent higher in non-RTW states ($23.93 in non-RTW states versus $20.66 in RTW states). Median wages are 16.6 percent higher in non-RTW states ($18.40 vs. $15.79).

https://www.epi.org/publication/right-to-work-states-have-lower-wages/

In summary, union dues are the fees paid by members of a union to support the organization’s activities and initiatives. These fees are used to fund collective bargaining efforts, improve working conditions, provide training and development opportunities, and support strike funds, among other things. While there is some controversy surrounding mandatory union dues, many workers benefit from the collective bargaining power of unions and the improved wages, benefits, and working conditions that they can secure.

If you’re considering joining a union, it’s important to understand the role that union dues play and the benefits that they provide to both the union and its members.

*Thank you for reading! If you have any questions or comments about union dues or anything else related to unions, please feel free to leave them in the comments section below.